Discovering the Secret History of Hungarian LGBTQI Life Under Communism

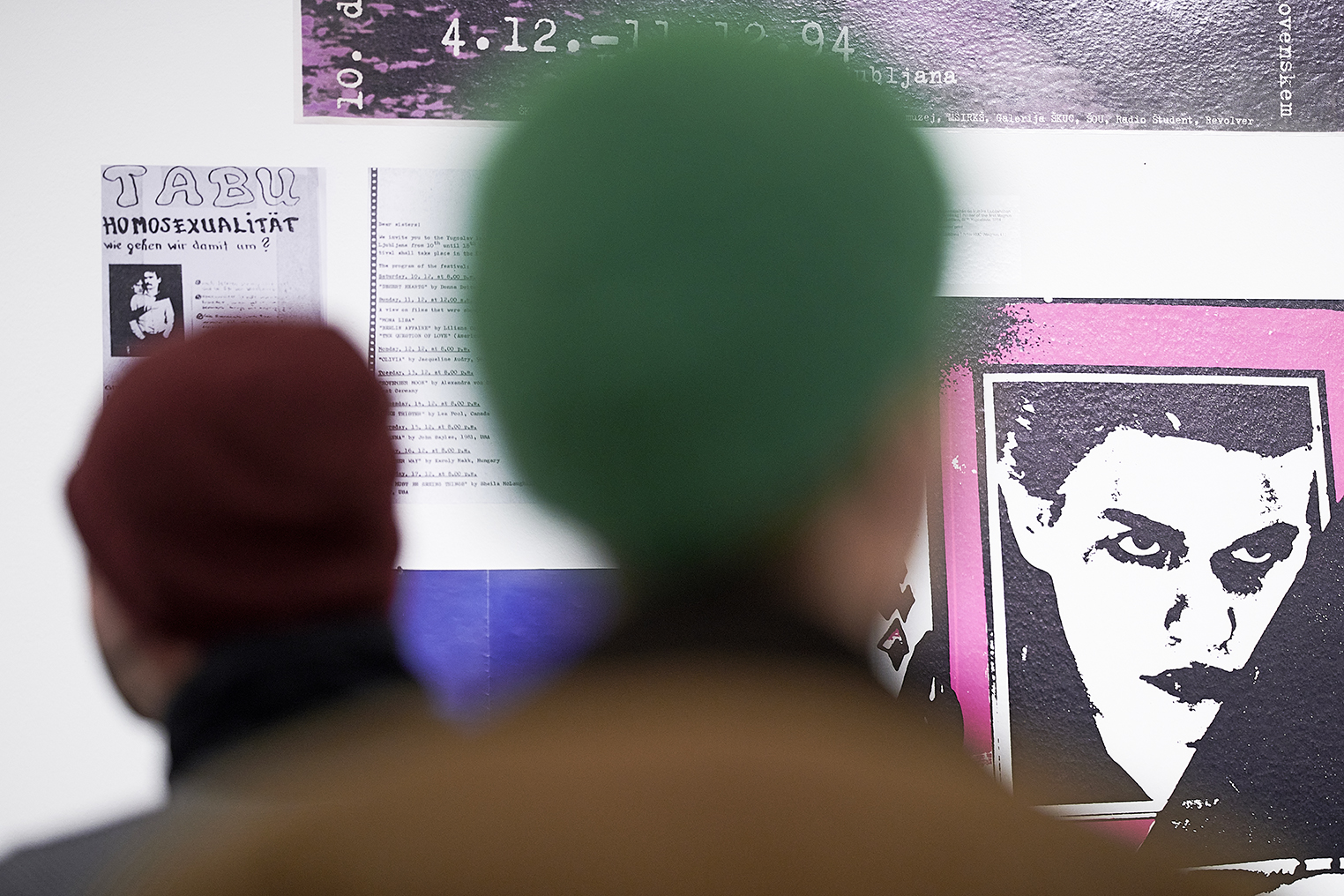

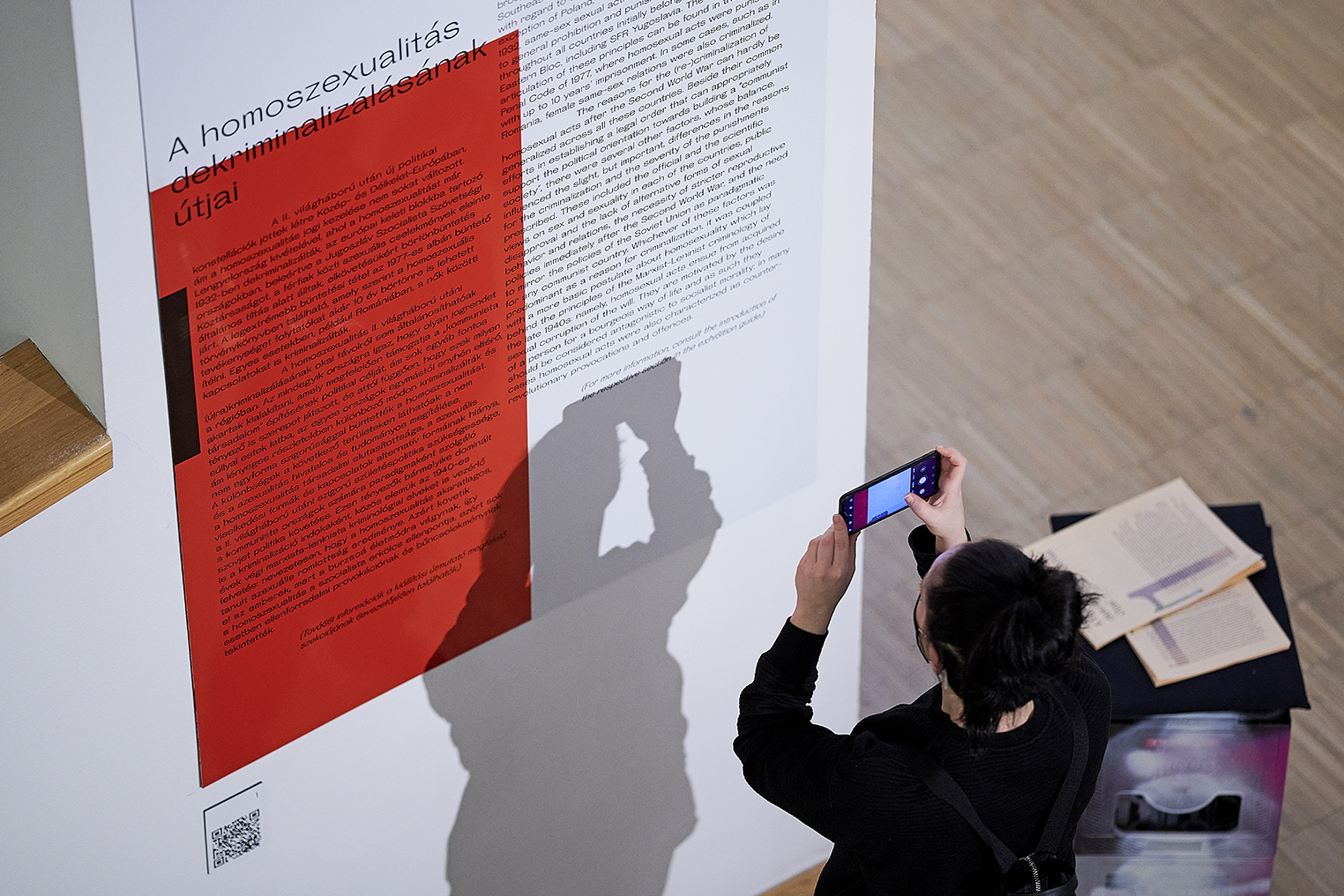

Photos from the “Records Uncovered” exhibition opening by Dániel Végel.

The Budapest Business Journal talks with Lajos Balázs Szabó, who has helped organize “Records Uncovered 2.0: LGBTQI+ Histories in Central and Southeastern Europe,” an exhibition that runs throughout February as part of LGBT History Month.

The exhibition is a collaboration between the Vera and Donald Blinken Open Society Archives and the Háttér Archive and Library. The Blinken Open Society Archives is one of the largest Cold War collections. It provides factual historical information to the public, fighting against historical revisionism and the misrepresentation of events of the past under authoritarian rule.

As part of its mission, the Hungarian Háttér Society, founded in 1995, preserves and shares LGBTQI (Lesbian, gay, bisexual, queer, transgender and intersex) heritage and culture. Szabó is part of Háttér.

“We are the oldest, largest LGBTQI organization in Hungary,” he told me. “Our contribution to the exhibition comes from our archive, which has existed since 1995. We collect books, films and LGBTQI ephemera, mainly focusing on Hungary and Hungarian topics. Our archive also collects historical documents from other LGBTQI organizations.”

The exhibition is an eye-opening insight into the lives of non-heteronormative people in Central and Southeastern Europe – the former Communist Bloc – in the last half of the 20th century. It includes legal documentation, media reports, private and institutional correspondence, artworks, and ephemera.

It covers countries that commonly shared two different political goals at two distinct periods: the establishment of a new communist society from the mid-1940s and the transition toward a democratic world from the 1990s.

There is also a program of movies and discussions. On Feb. 15, just after this issue is published, the subject will be “Connecting Gays and Lesbians Behind the Iron Curtain: the Role of HOSI,” which considers the history of LGBTQI activism in Central and Eastern European Countries.

Broad Scope

“There’s never been an exhibition with such broad scope, at least in Hungary,” Szabó told me. “It spans the entire former Eastern Bloc from the Soviet Union to Albania and covers subjects like the HIV/AIDS pandemic, how LGBTQI people self-organized, where they met and what their cultural life was.”

The exhibition was initially planned for February 2021, which would have been 60 years after homosexuality was decriminalized in Hungary, but COVID-19 put paid to that. When this exhibition could not happen in a real space, it moved online. It’s still possible to view via the web, but heading down to Centrális Galéria offers a far richer experience.

As Szabó says, “For this iteration of the exhibition, we put out a call for contributions and received a remarkable amount of fascinating material, including magazines, photos, diary excerpts, festival posters, videos and even copies of the 1980s Hungarian soap operas that featured gay characters.”

Szabó is proud that the exhibition’s broad scope makes it unique. “Even those who don’t belong in this minority will discover a lot of interesting information about the LGBTQI people under communism and after the transition in these countries.”

The history of LGBTQI rights in the former Communist Bloc, in general, is a mix of tolerance and repression. Although known to be homophobic, Marx and Engels didn’t have a position on homosexuality. In 1917, the heady days of the early Soviet Union, the Communist Party even decriminalized homosexuality.

But, in the early 1920s, especially in the Muslim-dominated Soviet Republics in Central Asia, homosexuality was still a criminal offense. In 1933, Article 154a of the Soviet Union criminal code made homosexuality a crime that could be punished by up to five years in prison. This law remained on the books until after the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1993.

Decriminalization

Personally, I was surprised, if not stunned, to discover that Hungary decriminalized homosexuality for men over the age of 20 in 1961. This was way before Britain, which didn’t pass the Sexual Offences Bill decriminalizing homosexuality between men “in private” until 1967. The U.K. bill was only amended to legalize homosexuality fully in 2000.

France, ever the pioneer, legalized homosexual acts between two consenting adults in 1791 as part of the French Revolution.

The first U.S. state to decriminalize consensual sex between same-sex couples was Illinois in 1962. Bizarrely, even though same-sex marriage is legal in all 50 U.S. states, gay sex is still illegal in 17 of them.

Hungary lowered the age of consent for gay sex to 18 in 1978. Apart from Hungary being a pioneer in decriminalization, I was surprised to learn from Szabó that the first truly independent NGO in Hungary was focused on homosexuality.

“The AIDS pandemic in the 1980s strengthened homosexual self-organization in the Bloc, which at first appears counterintuitive,” Szabó explains. “But, because it was mostly gay men who were becoming infected in the beginning, the Hungarian government and Communist Party realized that a gay organization would be far more likely to educate gay men about safe sex practices and encourage them to get tested,” he says.

“The government and party were acting for purely pragmatic reasons; they simply wanted people to stop spreading AIDS, but it was a major step forward for LGBTQI people in this country. And, don’t forget, this was before the regime change in 1989.”

Since it opened, “Records Uncovered 2.0: LGBTQI+ Histories in Central and Southeastern Europe” has received a steady stream of visitors, but is it mainly young people?

“Not at all; there have been quite a few older people,” Szabó says. “Some of them probably have personal memories of the material we have been exhibiting, especially those related to Hungary.”

The Centrális Galéria is at Arany János utca 32, 1051 Budapest. The exhibition is open Tuesday–Sunday, from 10 a.m.-6 p.m. It is not recommended for children below the age of 18. Find out more at the website osaarchivum.org.

This article was first published in the Budapest Business Journal print issue of February 11, 2022.

SUPPORT THE BUDAPEST BUSINESS JOURNAL

Producing journalism that is worthy of the name is a costly business. For 27 years, the publishers, editors and reporters of the Budapest Business Journal have striven to bring you business news that works, information that you can trust, that is factual, accurate and presented without fear or favor.

Newspaper organizations across the globe have struggled to find a business model that allows them to continue to excel, without compromising their ability to perform. Most recently, some have experimented with the idea of involving their most important stakeholders, their readers.

We would like to offer that same opportunity to our readers. We would like to invite you to help us deliver the quality business journalism you require. Hit our Support the BBJ button and you can choose the how much and how often you send us your contributions.