The Economic Vulnerability of Central European Economies

Two related phenomena may characterize today’s global economic scene: first, an “everything boom,” where virtually all asset prices have rapidly exploded in value, and second, steeply rising indebtedness, writes Les Nemethy.

Both these phenomena have been underpinned by extremely low interest rates, which have simultaneously fueled high asset prices and a massive debt binge, whereby governments, corporates, and individuals worldwide take advantage of central bank suppressed interest rates.

In finance, the concepts of debt and risk are inextricably intertwined. The more debt, the more chance of bankruptcy and default. It is almost a certainty that the current situation will finish badly; the big question is when?

Central Europe is not alone in its high debt levels. In 2020, the global average national debt surpassed 100% of GDP. Countries like Japan and Greece have spectacularly high national debts at 230% and 168%, respectively, although Japan has an incredibly powerful economic engine.

Total global debt in 2020 increased from 300% to 360% of global GDP, an eye-popping increase. The numerator of this ratio increased due to massive pandemic spending; GDP, the denominator, decreased in many countries, also due to the pandemic.

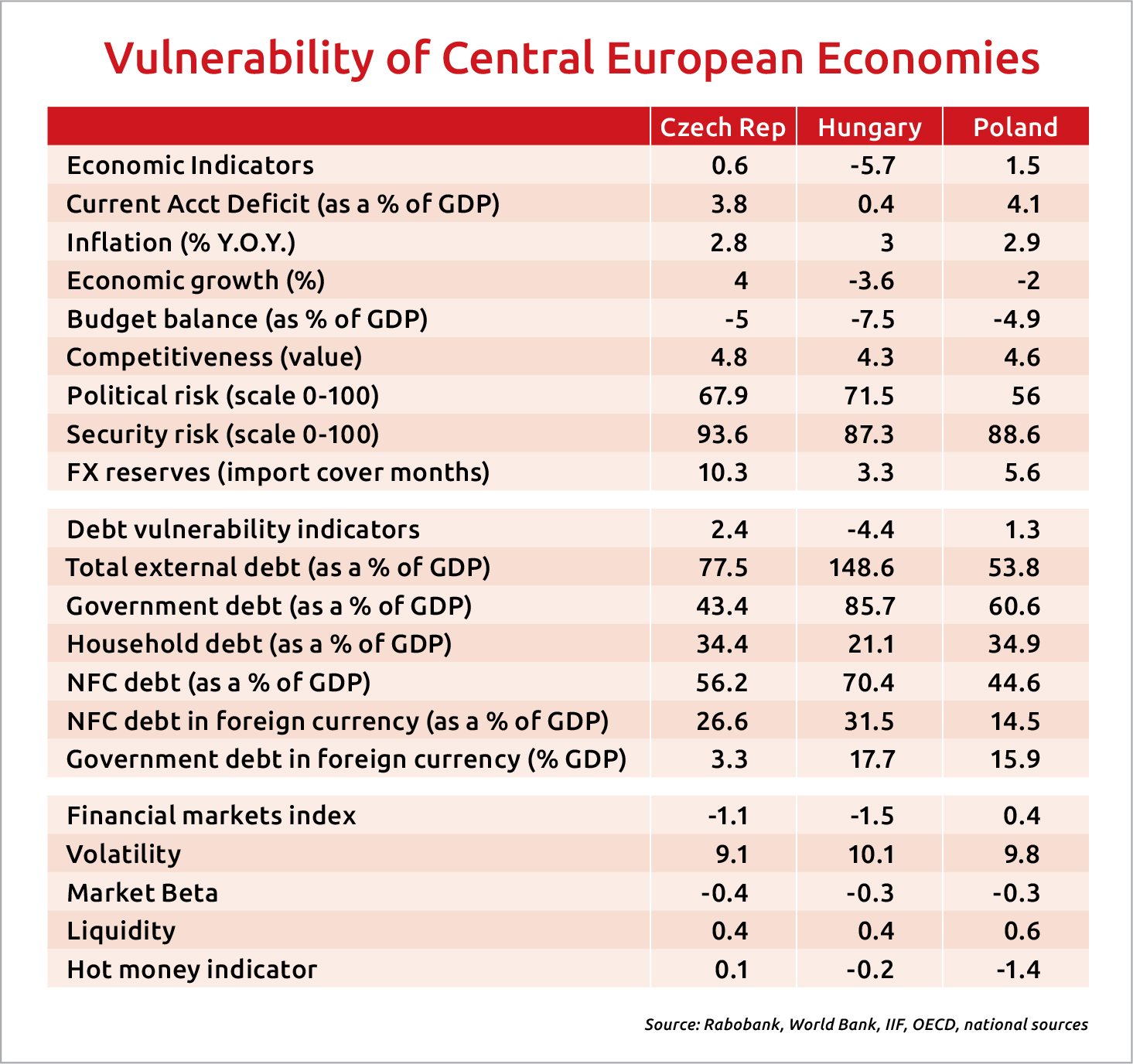

If we see the storm clouds approaching, we should batten down the hatches. In this column, we look at how vulnerable Central Europe might be to a potential economic downturn. We do this by providing the highlights of an analysis by Rabobank on Poland, the Czech Republic, and Hungary.

When the scores are aggregated, they provide the following results: the Czech Republic 1.93, Hungary -11.73, and Poland 3.23. While Poland and the Czech Republic receive marginally passing scores, according to Rabobank, Hungary is not only the weakest among the major Central European economies. It also has the second-worst performance among 20-plus global emerging economies ranked, after Argentina.

The poor Hungarian score is driven by high levels of total external debt, primarily government debt and debt of non-financial corporations (NFCs). A high percentage of debt is owed to external creditors.

Antifragility

As American financier Howard Marks said: “Financial [stability] doesn’t come from making or having a lot of money.[.…] You know what it comes from? Spending less than you make. Living within your means. It’s important to know that your antifragility comes from the extent to which you are not at the limit.”

This may be applicable not just for individuals but also for companies and nations. Most of the world seems close to the limit, some closer than others.

The world economy is integrated as never before; the contagion risk is enormous. This is why antifragility measures (for example, reducing indebtedness, denominating debt in local currency as much as possible, lengthening the tenor of debt) would be so important.

Over the past few years, in most countries, we have had the lowest interest rates in the history of the world. This is the only reason high debt levels have not led to default and crisis. Interest rates are so low they are lower than inflation rates in most countries.

If interest rates were to suddenly rise (in other words, a reversion to the historical mean of real interest rates), it would simultaneously:

1) knock the wind out of asset prices, meaning a possible collapse of financial markets, and

2) create failures in debt service, defaults and bankruptcies of individuals, corporations and governments.

Thus everyone, governments, corporations, and individuals, need to consider antifragility measures. The Omicron variant of the coronavirus may or may not be the next shock that hits the financial system, but mutations will not stop with Omicron. Sooner or later, there is likely to be a mutation that does not respond to vaccines. And there are numerous other non-pandemic “black swans” swimming out there.

Les Nemethy is CEO of Euro-Phoenix Financial Advisers Ltd. (www.europhoenix.com), a Central European corporate finance firm. He is a former World Banker, author of Business Exit Planning (www.businessexitplanningbook.com), and a previous president of the American Chamber of Commerce in Hungary.

This article was first published in the Budapest Business Journal print issue of December 3, 2021.

SUPPORT THE BUDAPEST BUSINESS JOURNAL

Producing journalism that is worthy of the name is a costly business. For 27 years, the publishers, editors and reporters of the Budapest Business Journal have striven to bring you business news that works, information that you can trust, that is factual, accurate and presented without fear or favor.

Newspaper organizations across the globe have struggled to find a business model that allows them to continue to excel, without compromising their ability to perform. Most recently, some have experimented with the idea of involving their most important stakeholders, their readers.

We would like to offer that same opportunity to our readers. We would like to invite you to help us deliver the quality business journalism you require. Hit our Support the BBJ button and you can choose the how much and how often you send us your contributions.