30 Years of Freedom: The Last Congress of the Hungarian Socialist Workersʼ Party - The Party’s Dilemma: Reform, Renew or Reject

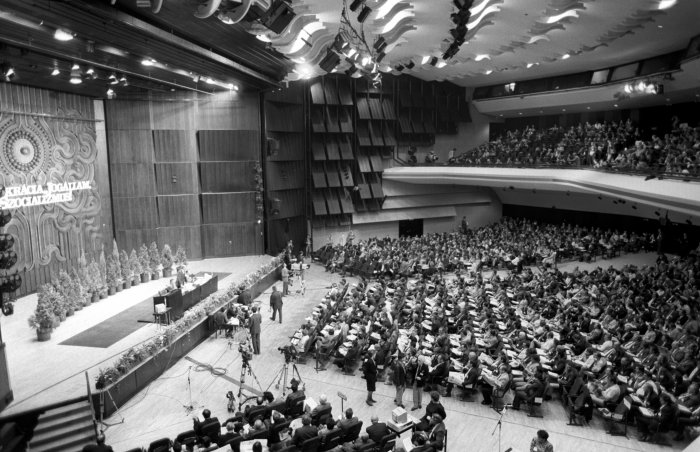

MTI/László Varga

The history of the communist state party, re-established after the 1956 Uprising and known as the Hungarian Socialist Workersʼ Party (MSZMP), had reached its final chapter in 1989. Renew the party, abolish the old or reject reform: this was what was at stake at the party congress convened in early October.

Delegates of the Hungarian Socialist Workers Party (MSZMP) meet at the Budapest Congress Center in Budapest on October 8, 1989. The congress was the last held by the MSZMP, and saw the birth of the Hungarian Socialist Party (MSZP) and the overtly communist Hungarians Workers Party (MPP). MTI Photo: László Varga

When the 14th MSZMP meeting took place in the early fall of 1989, it has been 16 months since Károly Grósz (General Secretary of the Hungarian Socialist Workers’ Party from 1988 to 1989) had successfully deposed János Kádár (who, as General Secretary, had presided over the country from 1956 until his “retirement” in 1988).

The change at the top of the MSZMP could not have happened without the consent of the Soviet Union; USSR leader Mikhail Gorbachev hoped his reform policy would find a supporter in Grósz.

At the time, the new general secretary was more concerned with who would bear the responsibility for the long overdue austerity demanded by Hungary’s economic crisis that had been escalating from the mid-1970s onwards.

A young 40-year-old politician, Miklós Németh was elected to serve as prime minister from November 24, 1988, a position he was destined to hold until May 23, 1990. However, Németh refused to play the role intended for him, just as Grósz had chosen not to dance in the manner Kádár had wanted before him.

Reformist Elements

Németh, Imre Pozsgay (Minister of Culture from 1976-1980, Minister of Education from 1980–’82 and Minister of State from ’88-’90 and Rezső Nyers (Minister of Finance from 1960 to 1962 and, for a few months in 1989, the country’s last Communist leader) were all much more pro-reform than Grósz.

Pozsgay cooperated most closely with the political opposition, Németh formed relations with the opponents of the MSZMP during the reburial of Imre Nagy and his companions, and did his best to create the image of a government of technocrats, rather than ideologues. Nyers was seen as a link between the Reformers and the Conservatives.

For the more advanced theorists and economists of the MSZMP, Nyers had a serious reputation as the author of what was known as the “new economic mechanism” in 1968 (subsequently dismantled between 1972 and 1974), while the party’s traditionalists trusted him as a founding member of the MSZMP.

Room for maneuver in the early autumn of 1989 was difficult to find, however, with the leadership of the MSZMP more than ever before constrained by the dynamics of the “shock” of the new era.

The political conciliation negotiations of the National Round Table (see “The Opposition Roundtable” in the March 27 issue) were laying the groundwork for a multi-party election. In addition, ever more strident calls were being heard in public for a referendum on what to do with the party’s assets, the abolition of the Workers’ Militia (the Munkásőrség, a paramilitary organization in the Hungarian People’s Republic from 1956 to 1989), the exclusion of party members from jobs and the best way to elect the president of the republic.

Internal Dynamics

There was an internal tension pulling the Socialist Workers’ Party in opposite directions: would the party leadership continue to operate on the basis of the roundtable discussions and various reform platforms, or revert to the ideology of the conservative “proletarian dictatorship”, “democratic centralism” and “class politics”?

Could “old school” party members such as János Berecz, Károly Grósz and Róbert Ribánszki, and the “reformers” led by Nyers, Németh and Pozsgay move forward together in the slowly emerging pluralist democracy under new and changed circumstances?

The conservatives were interested in whether the “reform communists” would remain or breakaway. The same question was asked by the reform forces, with a different emphasis, while yet more considered themselves neither reformist nor traditionalists. With all this internal tension, it seemed inconceivable that the differences of opinion within the party could be bridged smoothly.

There was enormous pressure on Németh. According to the prime minister’s recollection, Grósz had warned Németh in advance that he should prepare thoroughly before the congress because delegates wanted to hear from the PM the night before the opening what the government intended in terms of party assets, the Workers’ Militia and the party organizations in workplaces.

The prime minister found himself in a difficult position, judging that the reformers remained in the minority. Government decisions and their explanations were not accepted. Nor did many members of the party like the fact that, according to Németh’s plans, some of the property belonging to the party would be redistributed by the government among the opposition parties, so they could have their own headquarters.

October 8, 1989: From left, Imre Pozsgay, Minister of State, Gyula Horn, Minister of Foreign Affairs (later to become Hungary’s second democratically elected Prime Minister) and Miklós Németh, Chairman of the Council of Ministers at the final Congress of the Hungarian Socialist Workers Party (MSZMP) that saw the birth of the Socialist Party (MSZP) at the Budapest Congress Center. MTI Photo: László Varga.

Forerunner

On October 6, 1989, at the Budapest Convention Center, the 14th and last Congress of the MSZMP began. Above the dais, delegates could read a slogan in the spirit of the new times: “Democracy, Rule of Law, Socialism!” It was a foretaste of everything the future founders of the new party wanted to show to the public.

In his opening speech, Nyers addressed the risks of founding a new “democratic socialist” party, saying it would have electoral opponents with the same opportunities and constitutional guarantees who would look to support democracy without socialism. He explained that the new party could not be communist. But he suggested maintaining friendly relations with the reform communists, socialists and social democrats in both the East and the West.

His words in support of the creation of the new party were given particular weight because they came from one of the founding members of the MSZMP.

Secretary-General Grósz, although he too emphasized the need for reforms and “democratic socialism”, did not agree with everything Nyers had argued for. He stressed that there was no need to deny “communist ideals” and sought to put an end to the constant mention of the mistakes and sins of the past. He argued not for a new identity, but a renewed party.

Pozsgay, like Nyers, voted in favor of founding a new party, expressing the opinion that “despite all its values, the history of the MSZMP is the history of the party-state, the state party structure”.

Sensing that the membership of the MSZMP “carried the idea of reform”, he said it must create a new socialist party, with “the history of the MSZMP, together with the history of the party-state, ended at this stage.”

On the first day of the congress, it became clear that there were serious disagreements among the delegates. These continued to play out on October 7 as well. Then, on behalf of the “Reform Alliance” formed within the MSZMP, Iván Vitányi explained that something “radically new” must be formed from the old.

Legal Successor

He argued that the new party must be the legal successor, or at least one of the legal successors, of the MSZMP. For legal reasons, he said it was also a question of inheriting and taking over party property and infrastructure.

Finally, through the efforts of the People’s Democratic Platform and the Reform Alliance, the congress voted for the formation of a new party, the Hungarian Socialist Party (MSZP).

Népszabadság, the official organ of the MSZMP, had to react to all this as well. The next day, October 8, it published an extraordinary Sunday issue. The nameplate on the first page no longer carried the slogan of Marx and Engels, “Workers of the world, unite!”, replacing it instead with the words “Socialist Daily News”. That day the inscription “XIVth Congress of the MSZMP” was also removed from above the dais at the Budapest Congress Center.

Németh recalled that neither Grósz nor Berecz voted for forming a new party, nor did they join the MSZP. Nyers was elected its president. Ten percent of the delegates, 159 people, voted against its formation. This grouping held a renewed 14th congress a few weeks later, which is where the history begins of the Hungarian Workers’ Party, led by Gyula Thürmer (a communist politician and former diplomat who has been the chairman of the MMP since its formation on December 17, 1989).

Moreover, according to Németh, on the evening of October 7, reformers who were disappointed that those who voted against the establishment of the MSZP could remain in the congress in the raised the possibility of Pozsgay and Németh forming another social democratic party.

However, this was rejected; the prime minister did not want to risk the overnight government collapse that could be triggered by such a move, as it could not be judged how the MSZP would have reacted.

A Broad Church

Thus the MSZMP, unlike Gaul, was not divided into three parts, although the political differences among the delegates would have justified it. As a result, the MSZP became a broader gathering place for several left-wing ideologies, while doing its best to leave its Kádár-era past to the Workers’ Party.

The Socialists did not, however, become a mass party in the way the MSZMP had been; despite Népszabadság repeatedly asking former MSZMP members to join MSZP ranks, they did not. Thus the Socialists fought the 1990 spring general election with a few tens of thousands of members.

The new party would struggle with the past: the memory of the Kádár-era and the retaliation after 1956 had not been erased by the October congress.

But just as Németh had wrestled with Hungary’s economic inheritance, the party that won that first democratic election, the right-of-center Hungarian Democratic Forum, would also find itself facing difficult choices.

Four years later, the 1994 elections would see the Socialists, now led by Gyula Horn, the communist-era foreign minister who had cut the barbed wire border fence with his Austrian counterpart (see “Pan-European Picnic” in the April 9 issue) voted into power. But that is a story for another issue.

SUPPORT THE BUDAPEST BUSINESS JOURNAL

Producing journalism that is worthy of the name is a costly business. For 27 years, the publishers, editors and reporters of the Budapest Business Journal have striven to bring you business news that works, information that you can trust, that is factual, accurate and presented without fear or favor.

Newspaper organizations across the globe have struggled to find a business model that allows them to continue to excel, without compromising their ability to perform. Most recently, some have experimented with the idea of involving their most important stakeholders, their readers.

We would like to offer that same opportunity to our readers. We would like to invite you to help us deliver the quality business journalism you require. Hit our Support the BBJ button and you can choose the how much and how often you send us your contributions.