OECD on Hungary and Productivity: Impediments Must be Removed

The latest OECD survey delves into Hungarian productivity issues, including barriers to new market entrants, excessive regulation of professions and corruption.

Contrary to the impression created by the never-ending supply of upbeat government press releases on economic development, labor productivity in Hungary is not in good shape.

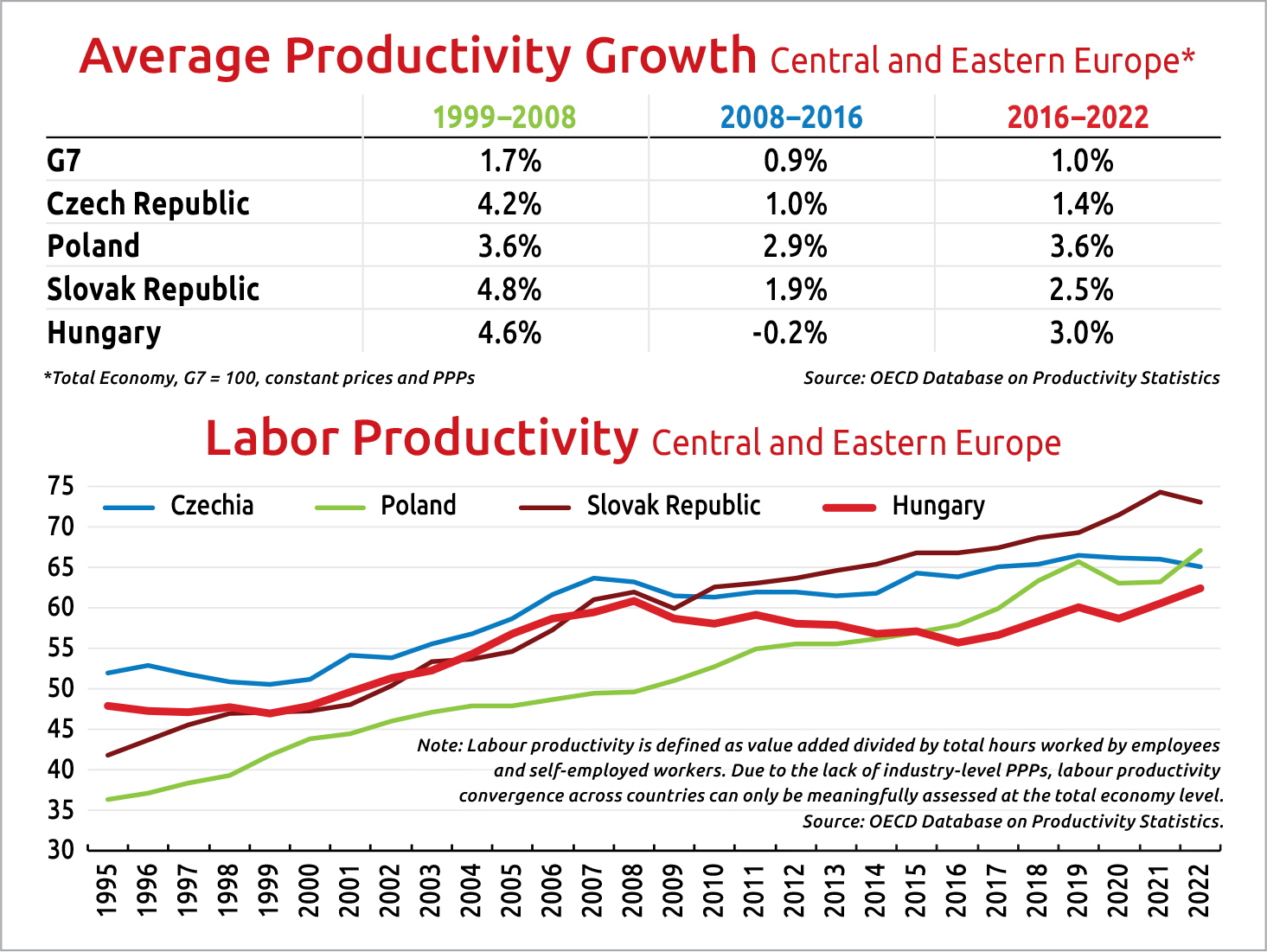

Indeed, after peaking at some 61% of the average productivity of the G7 just before the Great Financial Crisis in 2008, it then fell on average by 0.2% percentage points per annum to bottom out at around 51% in 2016, according to the latest OECD survey of Hungary, published on March 5.

Granted, since then, it has climbed back to close to 65% in 2022, but as the survey notes, despite growing at an annual average of just 3% since 2016, “labor productivity growth remains lower than before the GFC.”

The upshot of the intervening years is that, as of 2022, Hungary is the poorest performer in Central Europe in productivity, lagging Slovakia, the regional leader, by some eight percentage points.

As the OECD stresses in its introduction to the subject: “Labor productivity growth is the key to sustaining living standards. This is particularly important in the context of an aging population. Hungary’s working-age population is set to decline from 60% to just above 50% of the total population between 2020 and 2070 […]. This will weigh on GDP per capita unless productivity can be increased to compensate for this trend.”

In other words, Hungary must address productivity growth as a high priority, but how? The survey’s authors admit several hopeful developments, notably Hungary’s ability to attract foreign direct investment.

Automotive Transition

“The entry of new firms on a market facilitates the diffusion of innovations and can be an important source of future growth,” the authors argue. In particular, the influx of investment related to electric mobility will contribute to the transition of this sector to green technologies.

“Nevertheless, it is still too early to assess to what extent they will increase domestic value added and productivity in the long term,” the OECD cautions. The ultimate benefit to the economy will depend on the ability of domestic SMEs to contribute to the new value chains.

But aside from such potentially bright spots as electric mobility and auto manufacturing in general, the survey warns that business entry rates in Hungary are lower than in other OECD countries in almost all economic sectors, particularly in telecommunication and IT services.

Worse still, in most sectors, these lower-than-average entry rates are compounded by lower-than-average survival rates of new entrants in the first five years after their arrival.

True, the survey notes that administrative burdens relating to start-ups are low by OECD standards, with one-stop shops informing businesses about their license and permit issues, thereby cutting costs and establishment times. However, in some sectors, excessive regulation creates barriers to competition and market entry.

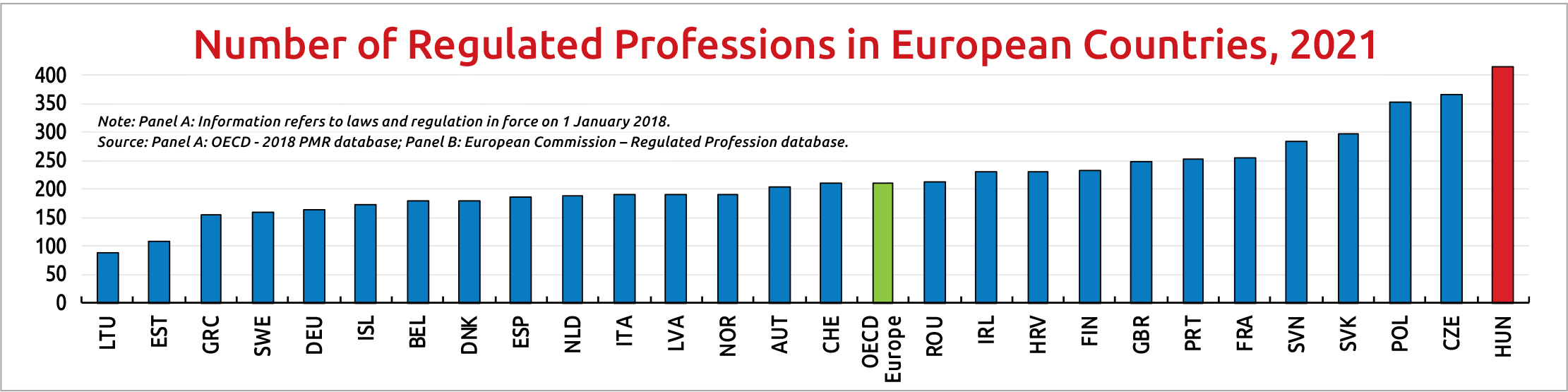

“The number of regulated professions in Hungary is the highest in any European country. For example, stringent regulations affect competition in legal professions such as lawyers and notaries, as well as water and road transport,” the survey stresses.

Indeed, it identifies more than 400 regulated professions in Hungary, twice the average within the European Union and four times more than Lithuania and Estonia, the EU’s least regulated countries.

The Absence of Pressure

The implication is that, protected by these barriers, incumbent operators in Hungary are under little pressure to innovate and reduce prices or improve competitiveness, to the detriment of long-term economic development.

By way of an example, the survey cites the case of the household retail electricity market in Hungary, where both the “strong presence of state-owned enterprises” along with current regulations and the uncertain regulatory environment “tend to hinder the entry of competitors.”

Moreover, the regulated prices (while politically useful for the government) “discourage competitors from entering the market as their return on investment would be insufficient” to justify their investment while simultaneously preventing new entrants from winning customers from incumbents by offering lower prices, the survey argues.

Not for the first time in its surveys on Hungary, the OECD recommends replacing blanket price caps on energy with targeted cash transfers to vulnerable households, arguing this would both increase the attractiveness of the Hungarian retail electricity market for new investors, contribute to efficiency gains and reduce the cost of targeted cash transfers for the government.

These barriers to entry inhibiting new market entrants contribute to another metric where Hungary performs poorly, namely the dominance of sectors by a small number of players. Indeed, when market dominance was measured on a scale of one (worst) to seven (best) at the World Economic Forum in 2019, Hungary scored just over three. This was significantly below the OECD’s average of 4.4, making Hungary the worst performer among the 38 countries assessed. (Chile headed the list, with a score of 5.8, followed by Japan on 5.6.)

As the OECD concludes: “The low entry and survival rates of new businesses are likely related to the dominant position of a few firms in Hungary. This, in turn, limits competitive pressure on incumbent firms and probably contributes to the fact that both innovation activities and business-financed research and development are low compared to other EU and OECD countries.”

Behind the Initials

G7: The Group of Seven consists of seven significant economies (Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the United Kingdom and the United States, plus the European Union) working as an informal forum of heads of state and government. It was formerly known as the G8 until the expulsion of Russia in 2014 following its annexation of Crimea.

OECD: The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development is an intergovernmental organization consisting of 38 members that works, in its own words, “to build better policies for better lives.” Hungary, together with the Czech Republic, joined the OECD in 1996. In February 2023, the OECD formally recognized Ukraine as a prospective member, committing to an initial accession dialogue designed to increase its adherence to OECD standards and participation in OECD bodies. Accession discussions were opened with Bulgaria, Croatia, and Romania (alongside Argentina, Brazil and Peru) in January 2022.

This article was first published in the Budapest Business Journal print issue of March 22, 2024.

SUPPORT THE BUDAPEST BUSINESS JOURNAL

Producing journalism that is worthy of the name is a costly business. For 27 years, the publishers, editors and reporters of the Budapest Business Journal have striven to bring you business news that works, information that you can trust, that is factual, accurate and presented without fear or favor.

Newspaper organizations across the globe have struggled to find a business model that allows them to continue to excel, without compromising their ability to perform. Most recently, some have experimented with the idea of involving their most important stakeholders, their readers.

We would like to offer that same opportunity to our readers. We would like to invite you to help us deliver the quality business journalism you require. Hit our Support the BBJ button and you can choose the how much and how often you send us your contributions.