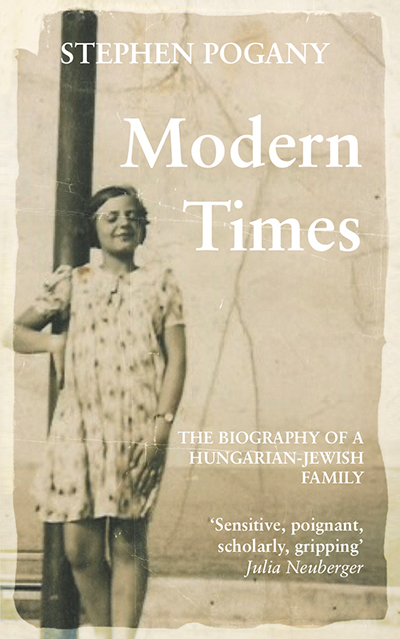

Modern Times: You Can’t Tell a Book by its Cover, nor its Bland Title

Stephen Pogany

War is awful; this is almost a truism, but that doesn’t make it any less terrible. As YouTube videos of Ukrainian soldiers struggling to survive the mud and cold in snow-filled trenches on the frontline illustrate, it’s a miserable experience, even without the constant threat of exploding ordinance ripping bodies apart.

And yet, even in war, there are sometimes surprising stories of decency. Take this anecdote, towards the end of Stephen Pogany’s “Modern Times,” related by his mother about the Budapest suburb of Zugló (District XIV) in late 1944, when Red Army forces were fighting their way, street by street, into the city.

“At one point, some German soldiers came down to the cellar and asked for the keys to our apartments so they wouldn’t have to break down the doors. They wanted to shoot at the approaching Soviet troops from the windows that faced onto the street. After their positions became hopeless, and they were in imminent danger of being encircled, the Germans carefully relocked the doors of the apartments, descending once more to the cellar to return the keys to their owners before making their escape.”

Not that Pogany, a Britsh-Hungarian professor emeritus in the School of Law at the U.K.’s University of Warwick, is any Nazi-sympathizer, far from it. His mother was at the time living undercover, in constant fear of being unmasked as a Hungarian Jew and likely murdered on the spot.

“Modern Times” might be as unimaginative a title as one could imagine, but its contents belie its bland designation. And the fact that the author includes this incident in his book shows a certain even-handedness in his writings. This gives the reader confidence that he is not merely on some ideological crusade, however much the events he describes might excuse such an approach.

Nor is this book primarily about war. Rather, it describes the day-to-day reality of four generations of two “ordinary” families of Hungarian Jews, Pogany’s progenitors, from the mid-19th century to 1946. Inevitably, however, the events of World War I impinge on earlier chapters and, given the families’ ethnicity, the orchestrated brutalities of the second global conflict dominate the later pages.

Pogany’s fascination with his forebears, however unremarkable they may have been, is perfectly understandable. But why should anyone bother to read nearly 300 pages about Hungarian-Jewish folk who seemingly neither invented nor created anything of note outside their immediate circles?

The answer is simple: Pogany uses his various family members to meander into all manner of Hungarian historical realities, both on the grand, political level and at street-cum-kitchen (and sometimes even bedroom) level.

More Overlooked

The former, of course, is what most historical tomes seek to address, certainly in English language publications; the latter is more overlooked and more difficult to access in anything other than a factual, data-driven way.

But through his family members’ experiences, Pogany helps readers feel the impacts of the grand, political and social changes, including those propelled by the hate-filled polemic of anti-Semite persuaders, at a very personal, individual and even intimate level.

Perhaps this is best illustrated by the life of Miklós, Pogany’s maternal grandfather, who, after serving as a dutiful patriot in the miserably equipped Austro-Hungarian army on the Italian front, came home crippled to face a life of unrelenting economic struggle, despite receiving a small pension on account of his war injuries.

In November 1944, Miklós was taken away from his temporary home by the fascist Nyilas militia, consisting primarily of Hungarian boys aged around 16. He was never seen by his family again.

Pogany’s forebears were involved in or associated with a vast sweep of activities over the years: the military apart, the reader thus dips into the lives of writers, football managers, innkeepers, poets and, of course, housewives, the latter often doing demeaning menial work on the side to survive.

The writer is perhaps at his tantalizing best in weaving both famous and infamous historical characters into the lives of his key family members. Thus, in chapter 11, he compares the lavish (if fictitious) menu in Zsigmond Móricz’s story “Lunch,” served for the well-to-do in rural Hungary, with the vitamin-starved, protein-less fare his mother grew up on in the 1930s.

“We only ate meat one day a week,” his mother told him in old age, “On Sundays, we had Wiener Schnitzel.”

We also learn how writers Cécile Tormay and Dezső Szabó fanned the glowing embers of anti-Semitism and, using what might today be called “fake fiction,” helped extinguish any memories that some 300,000 Jews, including 25,000 officers, had fought side-by-side with their Gentile comrades-in-arms for Austro-Hungary in WW I.

Hours of Research

As befits an academic, Pogany must have spent hundreds of hours researching evidence on the various claims of family members. He peppers his text with a myriad of references and explanations (almost all citing English language sources), which is of great help to those who may wish to delve further into the rabbit warren of Hungarian history.

The author is sometimes a little repetitive; most readers should know by chapter 17 (the final one) that maternal grandfather Miklós was “a disabled war veteran,” though, to be fair, it helps each chapter maintain integrity and reminds more forgetful readers of who’s who among the many characters that feature in the book.

As for accuracy, your reviewer could only question one of the author’s assertions with some confidence. Though Budapest developed rapidly after the 1867 Compromise with Austria, it is most unlikely that the city produced “the world’s first electric-driven railway engines.”

(This appears to be a commonly claimed Hungarikum falsehood, probably deriving from a distortion of Kálmán Kandó creating the globe’s first three-phase asynchronous motors, which were and are indeed used for rail use. However, German engineer Werner von Siemens is usually credited with the first working electric locomotive, at least outside Hungarian historical texts.)

When presenting the volume for review, Pogany revealed that he hoped to destroy the stereotype of Jews as wealthy bankers and factory owners living in luxury, in total contrast to the poverty-stricken masses struggling to put bread on their tables at night.

While there were undoubtedly some rich Jews (and Gentiles) in Hungary before World War II, it is abundantly clear from his book that the majority of the Mosaic faith struggled as much as any Hungarian Christian to better themselves between the wars.

Technical niceties aside, “Modern Times” is a highly readable, masterful insight into Hungarian history in the hundred years between the mid-19th and mid-20th centuries. Your reviewer thoroughly recommends it to those seeking to understand the vicissitudes of that era, and in particular, how so many in the majority Magyar population were readily persuaded into believing their minority Jewish compatriots were sub-human and should be exterminated without mercy.

If it were available in Hungarian, the book would be mandatory reading for all high-school students in an ideal world.

Modern Times: The Biography of a Hungarian-Jewish Family, by Stephen Pogany, ISBN 978-0-9931896-4-7, 283 pages, is available from Amazon and Best Sellers in Budapest.

This article was first published in the Budapest Business Journal print issue of December 1, 2023.

SUPPORT THE BUDAPEST BUSINESS JOURNAL

Producing journalism that is worthy of the name is a costly business. For 27 years, the publishers, editors and reporters of the Budapest Business Journal have striven to bring you business news that works, information that you can trust, that is factual, accurate and presented without fear or favor.

Newspaper organizations across the globe have struggled to find a business model that allows them to continue to excel, without compromising their ability to perform. Most recently, some have experimented with the idea of involving their most important stakeholders, their readers.

We would like to offer that same opportunity to our readers. We would like to invite you to help us deliver the quality business journalism you require. Hit our Support the BBJ button and you can choose the how much and how often you send us your contributions.